Workers’ strike in Milwaukee. Photo by flickr user Milwaukee Teachers' Education Association. January 1, 2014.

Is the best way to achieve higher wages really legislation? Many think so. Across the country, working people are eagerly waiting to feel the effects of new laws that raise the minimum wage. Seattle will see an increase to $15 by 2021, and Los Angeles will see the same increase by 2020. But this strategy detracts from the only power dynamic that can actually overturn economic inequality: class struggle.

Legislative wage hikes fade fast into inflated prices. Worse, they teach folks that ultimately we need not organize – except to ask the state to change things for us. That’s a losing battle on all fronts and one that obscures class analysis. This analysis says that there are two classes under capitalism, whose economically ordained conflict propels the system: the working class, who creates the surplus value in commodities, and the ruling class, who receives most of the wealth of commodities.

Instead of ceding our collective power to city councils and corporate offices, we need to broaden and radicalize the movement for a living wage, embracing more powerful tactics that today’s union leaders have dismissed. It’s not simply about the outcomes of reform; it’s about how we win it. That’s what teaches us how to fight. That’s what builds a movement. Without a movement, we have no hope for real, sustainable change. We have no hope of getting rid of capitalism.

If wage struggles are undertaken through strikes, work stoppages and occupations that physically keep out scabs—”replacement workers” who would take the places of strikers—struggles for higher wages can expose exploitation as the primary contradiction of capitalism. They can show that workers have the power to change the relationship between labor and capital and can teach class analysis on a scale that no college class can.

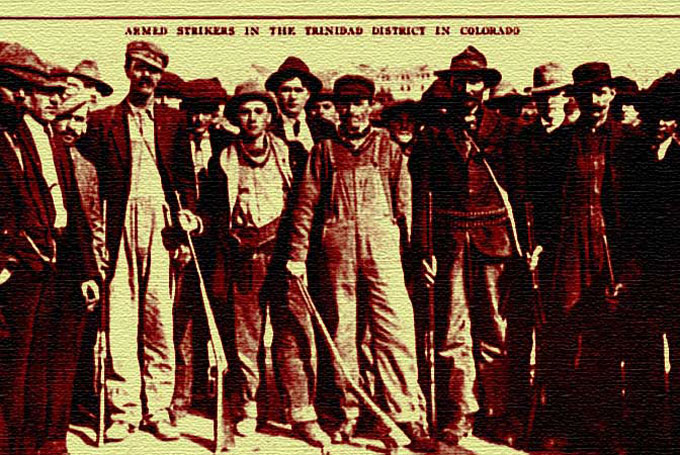

Armed strikers in Colorado, before the Ludlow Massacre. Photo by flickr user AK Rockefeller. 1914.

These tactics were used in the past: in 1945 and 1946 more than 4 million workers participated in the largest wave of strikes in American history. These strikes were so effective that in 1947 Congress, fearing union power, passed the Taft-Hartley Act to drastically restrict the tactics that organized labor could legally use, outlawing closed shops and strikes that affect whole industries, among other practices.

The left’s move away from class struggle is one of the legacies of the New Left movements of the 1960s. Throughout the 1910s and 1920s there were militant mining strikes in places like Alabama, Colorado and Montana – some involving armed strikers fighting company guns — and the 1930s brought occupations of factories in the Mid west. During this time the Communist Party USA (CPUSA) was influential in US politics through its members, “fellow travelers” or sympathizers, and ties to union organizers. The New Deal, the holy grail of liberal legislation, was put into place because the ruling class was afraid of the viable revolutionary movement in the United States.

In the 1940s, the Communist Party USA participated in the united front against fascism in order to defeat Hitler – simultaneously putting on hold challenges to the US government during the war. Revolutionaries no longer made public that they were revolutionaries, so as to maintain broad war-time unity. This, in turn, made the communist witch hunts of the 1950s very easy for the ruling class, as communist activity then seemed clandestine, rather than being out in the open as it had been in the past.

The McCarthy-era climate, revelations of atrocities committed by Stalin and the CPUSA’s weak response to both caused many splits within the party, and from these splits in the late 1950s and early 1960s came the beginning of the New Left. The New Left did things differently: no more showing people that they could stop the machinery of industry, forcing the bosses to meet demands or lose profit. Instead, their goal was to cause enough of a scene on the street that the media would cover it and embarrass administrators or politicians into meeting demands. This approach may have had some success at the time, but it’s not the model that today’s workers should use.

Our power lies not in the streets but at the pivot point of capitalism: the workplace.

I am hopeful about the new fast-food workers movement and the organizing at places like Walmart, but these struggles won’t succeed unless they eventually engage in non-symbolic, substantive solidarity strikes that target whole markets—in the case of retail outlets, these would be geographic regions, cities, counties, or sections of a state.

This would be illegal, yet necessary. Whole-industry solidarity strikes were made illegal precisely because they were extremely effective. Current unions stick to the letter of the law. This has made them very weak. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, 89% of US workers are not in unions. I believe this is because they don’t think the unions can win. And they’re right for the most part, but that’s where radicals come in.

I suggest that radicals create new, militant unions that are upfront about their revolutionary ideals, clearly articulating that winning fights around wage hikes through militant strikes is but one step in a revolutionary strategy. Declaring that we’ll physically keep scabs out will increase workers’ faith in their ability to win.

These new unions will break the laws that make current unions so powerless, and union organizers may go to jail. Jail isn’t new to radicals. An actual militant labor movement could organize a strike that is so effective that we negotiate wage increases and demand that the prices of goods be tied to corresponding wage increases, ensuring that wage hikes have real effects.

This sort of movement has the potential to be popular. It could lead to widespread general strikes to affect policy and develop from there into a situation in which the workers take over the facilities en masse. This would be the start of a revolutionary situation – one in which a living wage is a right, not a polite request.

The Coup perform in Chicago with the Overpass Light Brigade. Photo by Flickr user Light Brigading. February 8, 2014.

This piece, commissioned by Creative Time Reports, has also been published by The Guardian.